KV17 – STORY # 7 – SACRIFICING TIME

IN DANISH, KV17 IS SHORT FOR MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS 2017. ON 21 NOVEMBER, DANISH VOTERS WILL DECIDE THE POLITICAL COMPOSITION OF 98 MUNICIPAL COUNCILS AND 5 REGIONAL COUNCILS. THIS TAKES PLACE EVERY FOUR YEARS, AND ALWAYS ON THE THIRD TUESDAY IN NOVEMBER. THIS IS CAST IN STONE AND DIFFERS FROM ELECTIONS FOR PARLIAMENT, WHICH CAN BE CALLED BY THE PRIME MINISTER WITHIN THE PERIOD OF MAXIMUM FOUR YEARS. DURING THE ELECTION CAMPAIGN, I WILL POST A SERIES OF STORIES ABOUT SMALL AND LARGE ISSUES THAT DEFINE THE SPECIAL ‘DEMOCRATIC CULTURE’ OF MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS IN DENMARK.

STORY # 7

20 HOURS OF SACRIFICE FOR DEMOCRACY EVERY WEEK

All the statistics I refer to in this article is from the report “Kommunalpolitisk barometer 2017” [in Danish only], published by the VIVE center [VIVE – Viden til Velfærd. Det Nationale Forsknings- og Analysecenter for Velfærd]. The report is authored by Yosef Bhatti, Kurt Houlberg, Emil Thranholm and Lene Holm Pedersen and published in 2017.

Thousands of Danes have decided to participate actively in our local democracy by standing for election in the 98 municipalities. With an average size of a municipal council being around 25 members/councilors, this means that around midnight on 21 November, close to 2.500 persons will have been elected to a council to serve for a four year period. What motivated them to join local politics? Was it because of a genuine desire to contribute to our democracy? Or was it because being elected would result in getting an additional income?

I have met and talked to many councilors over the years, and my sense is that the majority of them decided to join politics because they really and genuinely felt it was the right thing to do, and an important thing to do, because in this way they could make a practical contribution to the improvement of livelihoods of people in the community where they themselves live. Some of them had it in the genes, because they came from Social Democratic or Conservative families, where grandfathers and uncles or aunts had once been a councilor, and one day it was their turn. Others had played roles in the local community in sports or commerce, and colleagues and friends had appreciated what they had done and suggested running.

This does not rule out that money can play a role, but for the large majority of candidates, it is definitely not the key incentive, and this is not surprising. After all, only the mayor of the municipality is a full-time politician with a full-time salary. For the other 24 councilors, serving as a councilor is basically a voluntary job, although the municipality offers a reasonable honorarium for those councilors who are elected chair of a committee, and there is some limited cover for participating in meetings. In addition, the municipalities own or co-own certain utilities [like water and waste management], and being the chair of the board or just a regular member of the board can result in some additional income. However, of the almost 2.500 people elected to the councils, my own guess is that only a small group of probably less than 10 percent will be able to generate what most of us would consider to be an income of serious proportions.

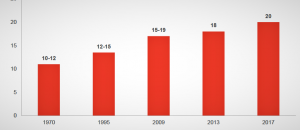

So because most councilors have a regular job, being elected as a councilor in a sense means that people ‘sacrifice’ part of their free time to make a contribution to our democracy. When the first surveys were made 50 years ago, the average councilor would need to spend around 10 hours weekly for preparing for and participating in council or committee meetings. Today it is close to 20 hours, as presented in the graph below. I am sure some councilors have reported more hours than they actually use, because over-reporting is a phenomenon we see in other surveys similar to this one, and it is a very human reaction. Still, it is safe to conclude that an average councilor will be spending at least 50 percent of a normal working week in the service of democracy, and for the large majority with a limited economic contribution.

Average number of hours spent by councilors on their job 1970-2017.

What exactly do people then spend the time doing? I will mention the different areas in order of importance: 4,1 hours to prepare for committee meetings; 3,2 hours for participation in committee meetings; 3,1 hours to prepare for the ordinary council meetings; 2,8 hours for other activities related to the job as councilor; 2,5 hours for participation in the council meetings; 2,4 hours to participate in meetings of the party; and finally 2,1 hours for conferences outside of city hall. One conclusion is that more time is spent preparing for meetings [7,2 hours] than for actually participating in meetings [5,7 hours]. While this may sound a bit strange to some people, it probably makes a lot of sense, because the issues being debated in the council can be quite complicated – in fact probably much more technical and complicated than 50 years ago.

Two questions then need to be asked to get a good idea of how the ‘democratic sacrifice’ impacts on the individual councilor and his or her family: Does the work as a councilor impact negatively or positively on family life? Does the big sacrifice in time invested and with limited economic compensation mean that the councilor is unwilling to run for another term in the council?

Regarding the first question of how the time spent on the job impacts on the private life of the councilor, the responses show the following results: 18 % say that it very clearly does influence their private lives; 30 % say that it does, to some degree; and 34 % respond with a yes, but only a little bit. This means that only 18 % clearly state that it has no influence on their private lives whatsoever.

With such responses to the question of the time you need to invest, you could expect that many councilors would hesitate to go for re-election. However, this does not seem to be the case. Almost 85 % of the councilors elected in 2013 state that they are ready to stand for election again in 2017. So neither the time required to be a councilor, nor the rather limited economic compensation offered, push people to give up. Actually, the percentage of councilors ready to stand for re-election has increased – in 2005 it was only 62%, and in 2001 it was 71 %.