ZIMBABWE 25 YEARS LATER [14]

30 MARCH 2018

QUALITY COFFEE FROM EASTERN HIGHLANDS – ONCE AGAIN?

Not all stories are equally important when you revisit after 25 years, but some of the ‘small’ stories can actually provide a perspective on the development the country has been through during the period since 1990.

I was reminded of this, when we walked into the Indaba Book Café in Bulawayo, and my wife spontaneously asked me if I remembered the coffee we used to drink in Harare. I finally did, with her help! We got fantastic coffee (roasted beans) from a farm close to Chipinge in Eastern Highlands, and we would then grind the beans ourselves.

The Indaba Café offered excellent coffee, in all the varieties that are common to all cafés all over the world. Running through the Daily News newspaper while drinking my cappuccino, I accidentally come across a small article at the bottom of a page with the following headline: “Coffee production in dire state”. The article offers a dramatic perspective of a small corner of the Zimbabwean economy, and it deserves to be shared with you. Here is a short summary.

The controversial agrarian reforms by President Mugabe started around 2000, and the most dramatic aspect of the reforms was the forced removal of white farmers from their properties. Officially presented as an exercise meant to redress past historical imbalances and injustices, it was effectively also a political card used to undermine the new political opposition coming from Morgan Tsvangirai’s new party, the Movement for Democratic Change.

By the way, I fully agree on the historical injustice argument. Unfortunately, the Brits did not allow this to be addressed immediately after Independence, as enshrined in the Lancaster House Agreement from 1980, and I have always believed that this was a mistake of historical proportions.

Around 3.000 large-scale commercial white farms were taken over, to the benefit of around 300.000 indigenous black farmers – as well as a large number of well-off members of the ruling party, many of these without any significant agricultural skills. Not surprisingly, this resulted in a fall in agricultural production, which contributed to the deep economic crisis, which Zimbabwe has still not been able to recover from.

Now, for the coffee sector, the following statistics are important: In 2004, there were 145 coffee farmers, farming an area of 7.600 hectares. Today there are only 2 commercial coffee farmers, producing on 300 hectares. In addition, today there are 400 smallholder farmers on 77 hectares, down from over 2.000 smallholders on 400 hectares in 2004.

This translates into the following production numbers: Coffee production peaked in 1989 at 14.664 tons, and it hits its lowest in 2010 with only 208 tons produced.

I am no coffee expert, although I wrote an educational book about the trade and consumption of coffee 30 years ago. Therefore, I do know that certain technical skills are necessary, if a farmer wants to produce high quality coffee that can compete on the world market. Remembering the quality coffee we got from Eastern Highlands, there is no doubt in my mind that Zimbabwe could again produce fantastic coffee for the benefit of coffee lovers around the world – and for the benefit of the farming families involved, white and/or black.

29 MARCH 2018

WILL THE BINGA CRAFT CENTRE SURVIVE THE CRISIS?

Driving up the bumpy tar road leading to the town of Binga, situated close to the shores of Lake Kariba, the first big sign built in stone tells us to take the dust road to the right if we want to visit the Binga Craft Centre. Which is exactly what we want to do. Not to visit as such today, but to see if we can make an appointment with a staff member to come back the next day to talk about the situation of the Centre.

We walk around the beautiful thatched-roofed buildings. Well, it would be more honest to say ‘the once upon a time’ beautiful buildings! The truth is that the thatched roof of one of the buildings is full of holes, with water on the floors from the recent rains. Nothing in this building indicates that there is any life left in this project. The state of affairs of the other building is better. Through the windows, we can see rows of files sitting on the shelves, but no telephone, no computers, and no staff. In another room, we can see the beautiful baskets woven by Tonga women lined up on a table. A flicker of hope maybe?

That night I did not sleep well at all, and the hot and humid air close to the lake did not cause it. The Binga Craft Centre was one of the projects closest to my heart when I lived in Zimbabwe. Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke invested a lot of energy, money and posting of development workers during my own time as Director, as did my successors in the following years. Was it now all over for the Binga Craft Centre? Had this ended up as a ‘white elephant’?

Leaving Binga the following day, I was a lot wiser, and slightly more optimistic. Not because the Binga Craft Centre is doing well, far from it. No, the optimism was caused by the Manager of the Centre, Mr. Matabbeki Mudenda, who took me through the history from the start in the 90s until today. He had been away for a funaral yesterday, and we had therefore missed each other. He started working for the Centre in 1997 (after working for the environmental CAmfire programme, which MS also supported), and he was appointed Manager in 2005. He came across as one of those extraordinary people, whose dedication and commitment to the idea of empowering thousands of women weaving baskets in this poor and remote part of Zimbabwe simply is unbelievable.

I will provide more details of this project in the book I hope to publish in 2019. Let me give you the highlights now! At its peak around 1997, the Binga Craft Centre had organized 3.000 women – meaning that it directly affected at least 15.000 people, when husbands and children are included. The economic crisis in Zimbabwe after 2000, culminating around 2008, with a rate of inflation surpassing anything seen in economic history, made it almost impossible to run a business selling baskets, despite the unique patterns and high quality. Ten years later, there are no more than around 1.000 women weaving baskets, the quality is not what it used to be, and the middlemen have come back, forcing women to sell at low prices.

Of course, politics has played a role as well. In good times, political forces have exploited the Centre. In bad times, it has not received the support it deserves. Undoubtedly, MS has also made mistakes – and I intend to be honest about those in my book. What amazes me is that Mudenda has stayed around, without really receiving anything you could call a ‘salary’. When a basket has been sold, 70 percent of the price is paid to the weaver, and 30 percent is kept for administration, including salaries. For at least ten years, Mudenda has received no regular salary!

Before leaving Binga, Mudenda tells me that he would like to write a book about the history of the Binga Craft Centre. I am slightly taken aback when I hear it. A book? However, I quickly realize that it is also a fascinating and appropriate idea, so I offer my support and suggests that we work together on this. The thousands of Tonga women, who have produced such beautiful products over the years, deserve to be recognized.

Of course, the Centre also deserves to survive. Mr. Mudenda tells me that he has just sent off an application to a donor, not asking for millions, just a small amount to allow activities to continue. The Manager may not get paid, but he still reports to work every day – despite the telephone line not working and electricity having been cut off, because the bills could not be paid. What is the right word for this?

28 MARCH 2018

MUSEUM IN BINGA TELLING THE STORY OF THE TONGA PEOPLE

“Welcome to the BaTonga Museum in Binga. You are most welcome. When you have paid the entry fee, I will take you on a tour of the exhibits in the museum.”

She is a 27 years old, she is Tonga, and her name is Lambiwe Munkuli. When I ask her about her obvious pregnancy, she tells me that she is set to deliver her second child, a boy this time, on 27 April, only a month from now. When I tell her that she was only two years old, when I visited Binga for the first time, she starts laughing and reaches for my hand, as is the custom here.

Back in the early 90s, I would travel by car to far-away Binga on the shore of Lake Kariba, at the end closest to fashionable and tourist-infected Victoria Falls. Getting there from Harare was a ten-hour tour de force over more than 500 kilometers on potted dust roads, when taking the most direct route. This was not an option for us this time, because we did not drive a 4-wheeler. We had to take the long route, meaning from Bulawayo to Binga and back, a total of 850 kilometers. The first part was fine. The last 80 kilometers was definitely worse than 25 years ago.

Some would call Binga a slightly wild west like town. There is not a single two-story building. Houses are dispersed over a large territory, and the whole area is very sandy. Temperatures are usually high, and so is the humidity, with the lake nearby. This is not a place I would personally like to live for many years with a family, if I had a choice. Nevertheless, we had several Danish families living here, posted by Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke as development workers – to support and build capacity in areas of health, environment, maintenance of schools, and culture.

This story is about culture, because Binga is the territory of the small group of Tonga people, although the third largest after Shonas and Ndebeles. Once upon a time, they lived along both sides of the Zambezi River in present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe. In the 1950s, government officials without consultation decided to flood the Tonga’s lands to create a dam at Kariba to produce hydroelectric power. The Tonga people were displaced from the river valley, rounded up, and relocated to the higher dry country, marred by low and erratic rainfall and poor soils.

There are probably about 250.00 Tonga people living in Zimbabwe today. While issues of livelihoods are important, MS agreed with the local authorities that it would be important for future generations to know the history that resulted in the Tonga’s ending up here, rather than living along the river, in villages now covered by the greenish waters of Lake Kariba.

Both emotionally and as a development professional, I have always felt that the MS-support to the Binga Museum was a meaningful exercise. We invested in studies conducted by museum professionals; we discussed the most sustainable structure of management necessary; we looked into how this could be a living part of what students learned as they grew up. In short: how could this be set up in such a manner that it was genuinely owned by the Tonga people themselves?

I will tell much more about my thoughts about this in the book I am working on for publication in 2019. Right now, I must admit that pregnant Lambiwe, the guide at the museum, made my day. I was actually wondering if the museum still existed. It does! Nothing fancy; not with hundreds of visitors paying an entry fee every day; not with lots of staff working to update exhibitions; but with Zimbabweans from other parts of the country – Libiwe told about school classes visiting all the way from Harare – as well as locals coming to visit. From the guest book, I noted that in recent years there had also been visitors from the UK, Germany, South Africa, and from Denmark the Hansen family!

26 MARCH 2018

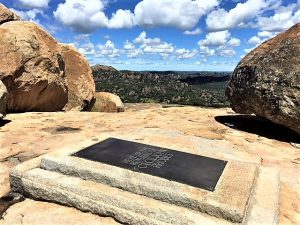

VISITING CECIL RHODES’ GRAVE IN MATOPOS HILLS

I know of few people, if any at all, who have been able to choose as magnificent a place to be buried as Cecil Rhodes – businessman, politician, believer in British imperialism and white supremacist. Together with his British South African Company, Rhodes ‘founded’ the southern African territory of Rhodesia in 1895. Driving through the Matopos Hills National Park, I am once again struck by the serenity of the unbelievable natural constructions of stones, sitting on top of each other, seemingly ready to tumble down if touched by human hand, but they are still there, more than two billion years after having been formed. Mzilikazi, founder of the Ndebele nation, gave the area its name, meaning ‘Bald Heads’.

Whenever I see photos of Rhodes taken around the time of his death in 1902, at the age of 48 years, my first thought is that I am surprised that he is not much older. He certainly looks much older, although probably not after the standards of his day. My second thought is that while I detest his ideas about the supremacy of white people and his description of black people as largely living “in a state of barbarism”, it is difficult not to ‘admire’ what he was able to achieve in a relatively short span of time.

Rhodes came to South Africa in 1870, when he was 17 years old. He entered the diamond trade in 1871, when he was 18. Over the next two decades, his company, De Beers, formed in 1988, gained near-complete domination of the world diamond market. Rhodes entered the Cape Parliament in 1880, and he became Prime Minister in 1890, at the age of 37. He ‘founded’ Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe and Zambia) in 1895, at the age of 42.

The site of his grave is a national monument. There are those who feel that his remains should be moved away from Matopos, because this is an area that the local Ndebele people call Malindidzimu – “the place of benevolent spirits”. Entering the gate and paying the entry fee, I ask the official what she thinks about that idea:

“Well, he was part of our history, like it or not. This will not change if he is moved to a different place.”

The official is right of course. Still, standing at the gravesite, trying to absorb the unique beauty of the landscape stretching as far as my eyes can see, I really feel that it is wrong for a person with his mindset to rest here. I am reminded of what he stated in his ‘Confession of Faith’ in 1877:

“We know the size of the world, we know the total extent. Africa is still lying ready for us, it is our duty to take it. It is our duty to seize every opportunity of acquiring more territory, and we should keep this one idea steadily before our eyes that more territory simply means more of the Anglo-Saxon race, more of the best, the most human, most honorable race the world possesses.”

25 MARCH 2018

A ZIMBABWEAN WITH VISIONS AND IDEALS

The main reason for our visit to Gwanda was that this is the place of residence for one of the Zimbabweans, who has been most important to us for our understanding of developments in this country. This is Paul Themba Nyathi, who was the first Chair of the Policy Advisory Board established by Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke (MS) in the first part of the 90s, as part of the MS in the South strategy. With the 75-year anniversary of MS coming up in January 2019, I decided to go to Zimbabwe and talk to him about his reflections of the role of MS during the first decades of independent Zimbabwe.

His thoughts about this will only be available for public consumption in January 2019. However, Paul is an interesting and impressive personality in his own right, and this is the first time we have the opportunity to meet him in his own environment. Before we always met in Harare, or in Copenhagen when he visited us in the 90s. We have not been together for at least 15 years, but still it feels like only yesterday we sat together and shared visions for Zimbabwe, as well as for the world at large. It is great to be able to do this again!

Paul is definitely worth listening to. Despite being only three years older than I am (he was born in 1946), his life has without comparison been more dramatic and challenging than my own. He is educated as a teacher, but he early joined the liberation struggle as part of Joshua Nkomo’s ZAPU forces. In 1976, this cost him three years in detention. After independence in April 1980, he continued to be politically active, but increasingly became pessimistic about the ability of the ruling ZANU PF party and devoted his life to grassroots work for ex-combatants and offering advice to civil society organizations – MS being one of them.

Towards the end of the 90s, Paul again became active in politics, and although you will not get himself to admit as much, my own understanding from what others have told me is that he played an important role in the formation of the Movement for Democratic Change, led by the newly deceased Morgan Tsvangirai. He was elected to Parliament for the Gwanda North constituency, and he became a hardworking and respected parliamentarian.

Today Paul is no longer active in party politics. At some point, he left MDC and Morgan Tsvangirai and decided to return to his grassroots. My sense is that this was a deliberate choice by a person, who is unwilling to compromise with the ideals that have driven him his whole life, since he was a young man. He is now the Director of Masakhaneni Projects Trust in Bulawayo, which is dedicated to supporting and empowering the weakest, the poorest and the most marginalized communities and women in particular.

24 MARCH 2018

THE PORTRAIT OF THE PRESIDENT

We have reached Gwanda in Matabeleland South province, after a 325 kilometer journey from Masvingo and Great Zimbabwe, through wide valleys covered in lush green after the rains, and mountains covered by green Msasa trees and dotted with magnificent stones, some of them standing on top of each other, looking like they are about to fall. However, we know this will not happen. They have been standing like that for tens of thousands of years, so why should it happen now. Why would the farmers build their homes and grow their maize right beneath the stone formations if they knew there was a chance the stones would fall and destroy it all. Of course not.

Gwanda looks like other larger towns in Zimbabwe – like Nyanga, Chipenge, Gweru, Kadoma, Mbalabala. The main road running into town is also the main street, with petrol stations, hotels, shopping malls, street vendors, bottle stores and much more situated along the street. For some few hundred meters, side roads extend to the left and right for a few hundred meters as well, allowing for a spider web like network of private homes behind solid walls or see through metal fences. In the pre-independence days, these were homes for white people. Today there are only few white families left in Gwanda. The houses now belong to black Zimbabweans.

One of the houses has been changed into the Apex Lodge, owned by a Zimbabwean couple. They wife and husband used to work in the banking sector, but they are now doing their best to make it in the hospitality sector. From what we experienced staying there for two nights, they have done well. We had a nice room with all the necessary facilities, we enjoyed the food, were treated nicely by the competent staff, and not least, we were able to spend most of our time in the garden, enjoying the trees and colorful plants, very similar to what we were used to in Harare in the 90s.

Of course, there was also a reception, and here we saw the obligatory photo of President Mnangagwa. In fact, this photo is the primary reason for and focus of this story! To tell the truth, it is difficult to comprehend that after having become accustomed to the portrait of Robert Mugabe, who for 37 years has looked down at his people as well as visitors to the country whenever they walked into a government office, a school, a bank, a shop, a hotel or a lodge, or any other building for that matter, Mugabe is no longer there! It is mind boggling. Now we have to get used to President Mnangagwa.

However, this is not the only thing, which boggles your mind. I will not lie and say that we have done a statistical survey of scientific quality, but we have asked a few people of reputable character how the change of portraits came about. This is what we know. It happened soon after the inauguration of Mnangagwa as President in November 2017, approximately one week after, give and take a few days. Photos of the President were distributed to institutions all over the country. Not only to this lodge in a large town like Gwanda, but to the most remote of rural schools according to evidence we have collected.

Why is this important or even remotely significant? Because it shows that contrary to the general belief among many, the authorities of this country are in fact perfectly capable of implementing a large-scale logistical operation, speedily and precisely. If this skill is put to good use in other areas, there is still hope for Zimbabwe.

23 MARCH 2018

THE MAGIC OF GREAT ZIMBABWE

Like in our own country, Denmark, history is important, and history can and will be used and misused. Not least used and misused by politicians to serve their own agendas. Just think of the Danish debate about our role in the slave trade from around 1670 to 1802, when close to 100.000 slaves from Africa were transported on Danish ships across the Atlantic, creating huge fortunes that helped build our capacity to develop as a nation. Or the war with Germany we lost in 1864, thanks to serious miscalculations by Danish politicians. Not to mention the way we handled the German occupation during WWII, which has been (mis)used by former Prime Minister Anders Fogh Rasmussen.

So it cannot come as a surprise that also in Zimbabwe, history is important for the self-understanding of the nation. Most often we hear about the colonial period that ended with the liberation struggle in the 60s and 70s and resulted in the declaration of independence, under the name Zimbabwe rather than Rhodesia, in April 1980. Less known outside Zimbabwe might be the pre-colonial period, with the historical monuments of Great Zimbabwe outside Masvingo as the most visible expression.

Great Zimbabwe is the largest of the stonewalled settlements which are found throughout moderne Zimbabwe, north-eastern Botswana and central Mozambique almost down to the Indian Ocean coast. It is one of the world’s most extensive dry stone wall complexes (i.e. built without binding mortar) and is comparable with the architecturally similar ‘ancient wonders’ of the Egyptian pyramids and the Inca sites of Peru. The settlement flourished between 1200 and 1500. It is thought to have been the capital of an extensisve ‘Shona State’. At its height, approximately 11.000 to 30.000 people lived at Great Zimbabwe, making it the largest ‘urban’ settlement in sub-Saharan Africa during its time. Well, there is much more to tell, but there is still also much which has not been explained.

We have been here before, but today we were lucky to be there with hundreds of young school children, who walked around and heard the stories of the past be told by guides and teachers. It is actually not an easy journey to walk to the top of the majestic stone mountain, where the elite of the settlement lived, and the children were visibly tired – as were we. From the top you can look down on the socalled ‘Great Enclosure’ (seen on the photo), where religious ceremonies and initiation of young girls took place, according to historians. But again, we cannot be entirely sure. Much still needs to be researched.

By the way, the bird in the flag of Zimbabwe was found here at Great Zimbabwe, carved out of soap stone. And the cone and phallus-like stone construction in the logo of the ruling ZANU PF party is found in the Great Enclosure. This became the logo in 1987, when the two liberation forces of ZANU and ZAPU merged. So history is an everyday part of the nation. Good to see students learn about this.

22 MARCH 2018

community based health care in birchenough bridge

When you move from the mountain areas of the East, in what is called Manicaland Province, and turn towards the West, into the Masvingo Province, you have to cross the Save River. At the end of the day, all the water in the Save river runs into Mozambique, and eventually it ends in the Indian Ocean. Compared to the amounts of water running through the Zambezi River or the famous Victoria Falls, the Save River is nothing to brag about. Nevertheless, it is the environmental lifeline for hundreds of thousands of people, and although the water flow has diminished, the breadt of the river is still impressive. Therefore, the monumental Birchenough Bridge is the only way you can get from Manicaland to Masvingo. Historically, it is one of the finest pieces of engeneering and architecture in Zimbabwe. It used to be open for traffic in both directions. Today, only one car at a time is allowed to pass. We did, and we survived.

Right on the other side of the bridge, you meet the township of Birchebough Bridge, a sprawling conglomerate of people selling whatever is required by the locals, and lines of taxis and mini-buses taking people back and forth over the river, as well as further into either Manicaland or Masvingo provinces. It was something like this 25 years ago. Today it is more of the same.

This used to be one of the places where Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke/Danish Volunteer Service (MS) posted development workers. Remember, in the 90s, the HIV/AIDS pandemic was one of the key health challenges. MS posted nurses to help with the organization of Home Based Care Programmes, because admitting all of those infected to the hospital was simply not an option. So Marianne was there, and Ellen was there. But would anyone remember? I turned right towards the hospital, after having crossed the bridge, hoping that maybe there would be a person there old enough to remember.

Right at the gate I met a nurse who seemd to be old enough to remember. Yes, she had been there in the 90s, and yes, she remembered. But it would be more appropriate for me to talk to the Matron, the administrative head of all the nurses at the hospital. So she kindly took me to Mr. Sithole, who happened to be in his office, and he was willing to talk to me.

“Yes, I remember Marianne, and I also remember Ellen. I was a junior nurse back then, and I remember playing the guitar with Ellen’s daughter, Anita. Back then we really needed the Danish nurses, and they did a great job. Today there are no expatriate nurses working here. We can manage ourselves today. By the way, today I live in the house that Ellen lived in back then.”

He was happy to talk to me, and he mentioned that Ellen had passed through 10-15 years ago on her way to Mozambique, he believed. We exchanged e-mails, and I promised to inform both Marianne and Ellen about my visit. Which I will do of course!

22 MARCH 2018

the sad story about chimanimani hotel

There are facts and figures that can be used to document the dramatic deterioration in the social and economic indicators for Zimbabwe, thanks to decades of failed policies, inadequate governance, and an unchecked level of corruption. This is not my personal judgement. This is in fact what newspapers write about every day right now. To some extent, it is also what is being admitted by President Mnangagwa, although it is not entirely clear who he thinks should be blamed. Among the statistics being mentioned, the 80 percent unemployment is probably the one that all citizens as well as commentators can understand.

However, the signs are clear in many smaller as well as larger ways. Like at the Chimanimani Hotel, some 250 kilometers south of Nyanga, not far from the border to Mozambique.

Nature has not changed since we stayed one night at the hotel back in 1994. The view towards the mountains is as majestic as ever. When the sun rises in the early morning, while the birds perform at their best, there is a yellowish-orangelike-reddish color on top of the mountain ridge. Flowers that we know in small sizes in our part of the world have gigantic proportions here in the garden. Lizards constantly changing color run across the floors and walls. It is almost hynotic.

The rest is sad to talk about. Carpets on the floors are falling apart. Ceilings are full of holes. Lamps in the hallways only work partly. The bar cannot serve a gin and tonic, because it has been impossible to get hold of tonic. Bread is not available in the restaurant, so the helpful young male servant runs out to get some. Like they had to do with serviets for dinner. Apart from the two of us, there are only two other guets eating and sleeping at the hotel. It is a wonder that the hotel is open at all, and that it can pay a salary to the staff. So I ask if more people are coming in over the next days and weeks.

“Yes, we have a group of 25 people from World Vision coming in for a seminar later today. But they will only be here for the day, and thy will have lunch. But they will not stay overnight.”

President Mnangagwa has given promises about change since he took over in November 2018. More investments will come in. More tourists will come to Zimbabwe. More jobs will be created. Livelihoods will be improved. Hopefully his government will be able to turn the situation around before the country reaches the point of bancruptcy.

21 MARCH 2018

the weavers in nyanga

“Ihhhhh, Mr. Bijoorn!” the tiny lady exclaimed, and standing on her toes, she threw her arms around me and gave me a hug worthy of a bear. The two other women sitting in front of the newly painted building followed, and amid laughter and clapping of hands, one of the women asked me: “Mr. Bijoorn, how is Hanne?” A natural question, considering that Hanne (a development worker posted by Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke) had been part of their lives on a daily basis 25 years ago. I had just been the boss from Harare, passing by once in a while for a project visit or an occasion of special importance.

Such an occasion had taken place in February 1995, when the 10 year anniversary of the founding of the ZUWA Weaving Cooperative in Nyanga had been celebrated, in the building where I am now meeting with Rose (on the left – 62 years old), Cecilia (in the middle – 57 years old) and Sheila (on the right – 58 years old). Rose was the one who gave me a hug to start with, and she was the one who gave me an update on the state of affairs of the weaving cooperative today, 23 yeaot herears after we first met.

“We were 20 members back in 1995. Since then some have died, and some have left for different reasons. All of us meet here at the building that we own every Monday. As you can see, we rent many of the rooms in the buildings to other companies and the Council, and this gives a steady monthly income. The rest of the week we come in groups every other day. As you can see, we are not doing any weaving, because there are no customers. So we come to look after our bilding, and on the days we are home, we take care of our garden and produce oions, tomatoes and maize to eat and to sell. Life is difficult in Zimbabwe.”

I remember the women working the large Danish wooden looms, producing high quality carpets with wool from local sheep, in beautiful whitish and brownish colours and simple but elegant patters. Some would be sold to tourists visiting Nyanga; some would be bought by the many Danes we introduced to this craft; and there was also some export. Today, there are few tourists coming to Zimbabwe in general, and local people cannot afford to buy the products. Those Zimbabweans who can actually afford it, will probably not consider bying this particular. They would rather buy something imported.

At the anniversary in 1993, we had managed to bring Minister Didymus Mutasa from the ruling ZANU PF party along as the guest of honour. I have no memory of what he said in his speech on the occasion, nor do I remember what I said. But I am sure that both of us hightlighted the strength and determination of the 20 women, and I believe we would have emphasized the idea of the ‘cooperative’ as a way of bringing both solidarity, jobs and improved livelihoods to the people. The cooperative idea was very much part of the ideology of the new nation that had been formed in 1980, and the cooperative idea was also very much part of the history of Danish development.

How does this all of this compare with the reality 23 years later? Well, only one third of the cooperative members are left. When the seven women of ZUWA die or retire, there will most likely not be anything left of the cooperative! Were we wrong, ignorant or misinformed, when back in the 90s, we decided to help this group of women? Should we have been able to predict the actions and decisions of selfish politicians, who ran the economy of Zimbabwe into the ground and made it almost impossible for an organisation like ZUWA to survive? I don’t know, but I am certainly thinking about all of these legitimate and necessary questions and scenarios. Hopefully I will have some sensible answers in the book I am planning to publish in the summer of 2019.

Leaving the three women, Rose looked at me, as if she could see the thoughts running through my head: “Tell Hanne that we are still here. Without the project and the building that we own, we would not have been able to send our children to school. Together, the three of us have 13 children, and they all got an education. Unfortunately, Zimbabwe has not been able to offer all of them a job.”

20 MARCH 2018

what is left of the half-way house

Today we left the capital Harare, moving 275 kilometers towards the Eastern Highlands, where majestic mountains form the border towards Mozambique. In the early 90s, we visited this beautiful part of the country several times, on vacation with family and friends visiting, and for project visits to partners and development workers, as well as training seminars and annual meetings.

Midway on the four hour tour, we would stop at the ‘Halfway House’ in Headlands, to stretch our legs, buy soft drinks and tea and coffee, and rest in the shadow of the enormous tree, which fills almost the entire area of the courtyard. The tree is as impressive as ever, seemingly untouched by the tear and wear of the weather and the never ending social and economic crises of the country – a situation largely created through the mismanagement led by politicians more interested in taking care of their own bank accounts, rather than making an honest effort to provide jobs and security for the people.

But almost everything else at this place tells this sad story. The shop used to be full of local produce, vegetables as well as cheese and meat; today all you can buy is a few varieties of water and soft drinks, a few types of biscuits, and ‘Bounty’ chocolate. The huge selection of trees and flowers for the garden has disappeared. The thatched roofing shows signs of wearing down, and in the corners of the once beautiful colonial type buildings, you see stones falling to the ground. Surprisingly, in the midst of the decay, the small restaurant serving coffee, toasted sandwiches and chips continues to operate, with the two women making up the staff going at it as if nothing has changed – they made us cups of great coffee and served us with a smile.

There was one other couple in the courtyard, and it turned out, believe it or not, to be a Danish couple. Like Anne said to me: “Fortunately we did not say anything that could not be quoted!” We thought we could easily boast of a history with Zimbabwe much longer than they could. No! The lady told us that they had come to live i Zimbabwe in 1980 and had lived there ever since. They worked for ‘Humana. People to People’, which is the name for what in Denmark we used to know as the Tvind Organisation. HPP has a huge international headquarter in Shamva outside Harare. Which reminds me that when one day the history of Danish activity and influence in Zimbabwe is written, it will be difficult not to award a significant position for HPP, whether we like it or not.

19 MARCH 2018

the life of clara

We did not recruit Clara to help us in the house, and not least with our two children, Thea and Lasse. She was there when we came to Harare, taking over the job as Coordinator for Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke after Vagn, his wife Dorthe and their three children. We arrived in June 1992 (on the same day that Denmark won the European Soccer Championship) with Thea being two and a half years old, and with Lasse inside Anne – he was born on 15 November 1992 at Avenues Clinic in Harare.

Since the first day he was brought to the house, Clara took care of Lasse when she got the chance, looking after him when Anne was not around, playing with him on the floor. You could argue that Lasse had two ‘mothers’. Whenever I have met Clara over the years, her first question has always been: “How is Lasse?” Of course, she would also ask about Thea, but Thea was old enough to manage her own life, playing in the garden with Luca, and in the kindergarten she went to.

Looking at the photos we had brought for her, Clara had a hard time reconciling her memory of Lasse as he grew up during his first years, and the bearded engineering student of 25 standing next to his girlfriend in the Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen, and also next to Bodil, Anne’s mother of 92 years, who visited us in Harare back in 1993.

Listening to Clara, it is evident that the years with the three Danish families she worked for in the 80s and 90s were good years. Not that she was paid extravagantly or much more than other household staffers were in Harare at the time. Her room in the shed behind the house was definitely not luxurious in any way – we often discussed if it was good enough! But she felt appreciated for the work she did, she was treated with respect, and she once told me that she felt that we trusted her. Which is true. Her English was not particularly good, and she would normally speak to the children in Shona, but once she had understood what we wanted her to do, we knew it would be done. And we always felt safe with her taking care of the children.

Now Clara has retired. Not because she wanted to, but because she has realized that no family is ready to employ a housemaid at the age of 70. Her last family told her! And after having served in the house of other families her entire life, she is now taking care of her daughter Rebecca and granddaughter Shalom. She has settled in an area – what some would call a slum area and others maybe a ‘growth point’ – around 20 kilometers from the City of Harare. Before she retired, she was smart enough to join a cooperative – Clara may not be well educated, but she is not at all ignorant or stupid. This membership provided her with a piece of land to build a house, and over the last ten years or so, she has slowly been able to pay for bricks and labour to get the structure built.

This is the house you see Clara and Anne posing in front of. Right now, she has one room she is using as a living room – and also preparing the food when it cannot be done outdoors. Another room is used for bedroom for the three of them – but it still needs to have a proper window frame put in. A third room she rents out – which brings in some necessary cash. The two rooms for toilet and kitchen are still not ready – she needs additional funds to finalize this part. Like other families in this area, and in other similar urban areas, she uses every inch of land not covered by buildings for agriculture, in this case mainly maize.

But one day she might just build on it. Clara may be old and she may be poor, but she is in her own low-key way very proud of what she has achieved. Living with a family like ours, she knows very well that there is a world of difference between our lives, Lasse’s and Thea’s lives, and her own life and that of Rebecca and Shalom. But you will never hear her complain. You will never hear her get angry. Maybe that is one of the things in life I still fail to fully understand. Why not?

18 MARCH 2018

the people who helped us in the 90s

Nando’s Restaurant in the Avondale Shopping Centre, not far from where we used to live, was the first stop down memory lane: to meet with the two families who helped us in the house (Clara) and in the garden (Batsirai). Back then, in the early 90s, it meant that five people lived in the two staff or servant rooms behind the house – Batsirai (born 1950) and his wife Maria (born 1950) plus the two boys, Wilson (born 1980) and Luca (born 1989). So the parents are Bjørn’s age, Wilson was 12 when we arrived in 1992, and Luca was almost a year older than Thea at two. Clara was on her own, her husband died years back, and her daughter Rebecca stayed with family down in Gutu.

Today we needed a much larger table for our lunch. Maria and Batsirai were there, together with Wilson, who is now 38 years old, and his wife Susan (they were married in 2006). Together they have three charming children: Melissa (born 2007), Masimba (born 2011), and Maria (born 2015). Clara (who has just turned 70) had taken her granddaughter Shalom (born 2009) along. So we were a total of 11 people around the table.

However, we could have been 15 around the table. Unfortunately Luca could not be with us. He married last year and now also has a son called Douglas. They have moved away from Harare and settled outside Mount Darwin, where he has taken over the farm originally owned by Maria’s parents. On Clara’s side, her daughter Rebecca could not be excused from her duties for the family she is serving.

What we talked about? What families who meet anywhere in the world talk about: How is Anne’s mother doing? How is Bjørn’s daughter in New York doing? How is Anne’s brother Per and Bjørn’s sister Sølvi doing? We were surprised that they could remember the names of literally all the people who visited us over the three years, family as well as friends.

And NO, we did not venture into a debate about how Zimbabwe is doing after the dramatic changes in November 2017, resulting in the fall of President Mugabe and the rise to power of President Mnangagwa. Still, from the adults we could feel a sense of relief, a bit of optimism, and a hope that the future could finally be better than they thought a few months ago.

16 MARCH 2018

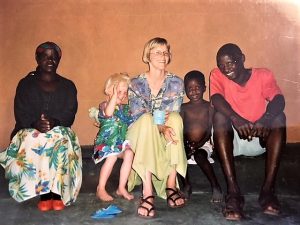

travelling down memory lane

Today, together with my wife Anne, I embark upon a tour down memory lane in our beloved Zimbabwe. We plan to visit people and places all around the country. We will start in the capital Harare, where we lived in the area called Strathaven, not far from the city centre. Then we will drive to Nyanga, and continue to Chimanimani, Buhera, Masvingo, Gwanda, Bulawayo, Nkayi, Binga, Gokwe and Nembudzia – weather permitting, in particular the rainy part of the weather, which can make some of the roads difficult to navigate (we will not be driving a big 4-wheel drive). All of those places are villages and towns where we visited regularly 25 years ago – because this is where Mellemfolkeligt Samvirke (MS) had development workers posted. Of course we will also spend time with the families that helped us in and around the house back then. In the photo you see Anne (who no longer smokes) and Thea (who is now 27 years old) in the rural home of our gardener and his wife, together with Luca (today also 27), the best playmate of Thea. Unfortunately they had to give up the house they built themselves years ago, because of ‘problems’ with the title deed, so today their home is on the outskirts of Harare, just like Clara does.